In a Nutshell: Alastair Eales

As part of our commitment to local creatives we are using this time to get to know the Winchester scene a little better! Our ‘In a Nutshell’ interviews are aimed at local creatives, practitioners, freelancers and independent businesses residing in Winchester. We want to use our platform to meet new people and showcase the incredible talent residing in this city. Henry caught up with artist Alastair Eales - they spoke about Alastair’s artistic journey and his work with Trinity, a drop-in centre for homeless people in Winchester.

Alastair Eales is an artist based just outside of Winchester. He achieved his BA (Hon) in Fine Art: Painting at the Winchester School of Art in 1999, before moving to Barcelona to pursue his MA in European Fine Art in 2000. His art practice mainly revolves around the idea of “art and community” and the exploration of the artist’s role within the charity sector and the wider community. He views art as being a direct conduit to the exploration of the human condition; the role of art educator has a symbiotic place alongside science, technology, engineering and maths.

Henry Morris: Can you tell us about your background and your creative education and experience? What has led you to this point?

Photo Credit: Alastair Eales

Alastair Eales: I did my BA in painting, and then I managed to get support and funding to undertake my MA through Southampton University - the Winchester School of Art campus but in Barcelona. So I did my European Fine Art MA in Barcelona. It was while I was there that I started to explore this idea of more participatory engagement and work. I say that - what I actually started doing was making cardboard dens to hide in. We would get roasted and lambasted by the lecturers that came round complaining that we were spending more time in the Barcelona hostileries than in the studio, so my den was my inner sanctum!

I actually grew up in Cape Town, in South Africa. My dad is English; I left when I was nine, so that’s 1983, right at the height, almost the height of Apartheid, just before the country went into emergency. It was a terrible time. For me, the cardboard den was also a stark reminder of seeing the poverty, the inequality. I remembered that even as a child, even though I couldn’t quite put that into a semblance of a real sense. I just remember it being really unfair.

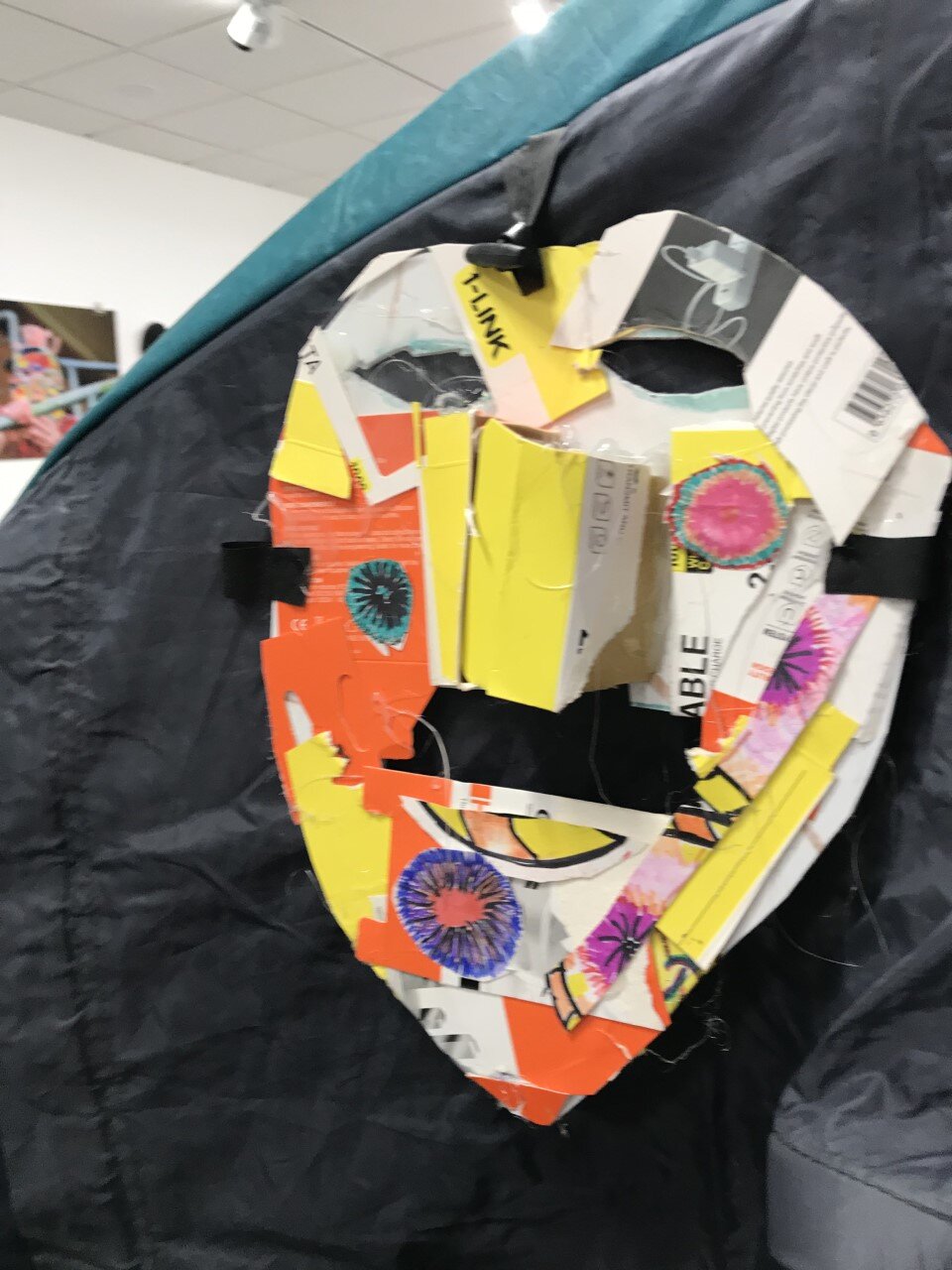

And so I had this object [the cardboard den] that could shift it’s meanings. What I realised with the object - it took different people to engage with the things I was making, these dens, these cardboard constructions - they would come in, they would read a different interpretation. So this thing, this object changed depending on the groups coming in. I realised that this audience participation was really vital to my own practice.

I get the MA, [...], I went to art centres, I went to theatres. I managed to get an artist-in-residence at Winchester Theatre Royal. With the youth theatre directors, we made these cardboard constructions, and each group that came in breathed a new narrative. So the little ones came in and they said they built dracula’s castle. Then the older kids came in and said ‘this is an eco-warrior’s den’. The same object - the collection of cardboard props - became these other things. The children would play, engage, participate, and that would add to the narrative, and then the narrative would trigger new objects to be added.

The idea of [...] whether you can make art but if it’s never seen is it art...some say yes and some say no. If you put something out, if you have a space - like The Nutshell perhaps - if you have a space where you engage, that thing becomes a fire, and it burns, and it creates new ideas, and becomes something more and it has a residence and it has a legacy.

Photo Credit: Joe Cooper

I started to think about working with the homeless, and working with isolated groups. I worked with community centres, children that were referred through the centres - young carers or foster kids. And then I hit upon Trinity Winchester in it’s old guise which was a much smaller organisation nestled behind The Winchester Railway in this dilapidated building, and I approached them with an idea to run an eight week project where I would come in and engage the wonderful audience and they would make this amazing art.

I was reading about - I think it was Public Health England - they were talking about how not one agency can solve the problem of homelessness. That it takes lots of different agencies. So I thought, as an individual, as an artist, what can I do? So I set up TAG - Trinity Art Group - off the back of this eight week course. I was meant to just go in as a freelance art educator. I took a teaching qualification [...] and it’s just grown. That was in 2001.

[...]

There isn’t a hierarchical way of art. You can have a scribble, you can have an architectural drawing. There is no right or wrong way. It means it’s inclusive.

HM: Such breadth of amazing information. What amazing work, especially with Trinity, which does so much work for vulnerable people.

Photo Credit - Alastair Eales

AE: I tend to like meeting people, and when I started the Trinity art group I had my own prejudices about who I was expecting to meet and what the people would be like, and all of those completely exploded. The group that I have now, some of them have been with me for quite a few years. This is part of their identity. It gives them a new label. Instead of ‘mental health’, or ‘suffering from long-term unemployment’, or whatever the malaise around their issue is, they can say, ‘I’m a creative, I’m an artist, I’ve got somewhere to go to. I’ve got a network of support from fellow creatives.’ [...] It shows that art is a really vital thing. It extends beyond what’s written on it’s tin.

HM: It must feel very empowering for people who work with you, to create things for themselves.

AE: The sense of ownership, the sense of responsibility. It really is empowering and what Trinity does rather well is that they do try and get people to aspire, and change and improve one’s condition and one’s chances in this world. In many cases we see people come into the group and then move on.

[...]

The resources that come from us bleed out to all of us. Social art needs to be collaborative.

HM: Well it needs to be truly social doesnt it.

AE: It does! We need to support each other. We need to make something so that it’s viable to go away and eat and have this place and have a way of generating an income. What seems to be the model before is that you have resources and you hold them to yourself and don’t share and they dwindle. But if you share, I think things spawn out of that.

HM: Can you talk a little bit about how you ended up in Winchester in the first place?

AE: My parents were worried about Aparthaid, worried about what the situation was. My dad was given two job offers, and unbeknownst to me and my brother, the two options were Southampton, or Sydney. My dad went for Southampton! I did venture out to Barcelona to live and study there for my MA, but I seem to be one of those homebodies - I’ve returned to Winchester. My wife was born in Winchester, and now we live just outside Winchester.

HM: Do you feel like there is something which you consider to be missing in terms of the artistic community [in Winchester]? Do you feel like there is a lack of something or a gap for something which you would like to see?

Photo Credit: Joe Cooper

AE: I’m particularly fond of Winchester. Winchester is very lucky; it’s very small but it has two universities, and both of them provide creative outlets. We have people who come to Winchester who are very creative, and some of them stay, and so really there does need to be a central point, or at least a network of things where it’s connected. I think that The Nutshell seems to me a really good idea right now.

I do think the idea of socially engaged art, and this idea to connect and the idea of communities becoming more relevant - especially in contrast with Covid-19 and lockdown.

Let’s say the hub is The Nutshell. It is in its essence a socially engaged space, by its nature. Why can’t this be something that the collective could then push out? Art doesn’t have to be local, it can be global as well.

HM: I can really see the Covid-19 situation accelerating the need and widening a gap for socially engaged art. If there’s one thing we’re all sick of it’s not being able to see our friends and our family, and I think it provides a need, not in an exploitative way but in a very hopeful and fulfilling way.

AE: In a strange way, more people have now gone through this idea of isolation; they might be more sensitive to many of my group who were going through all this isolation before lockdown.

HM: That’s a really good point. It’s been great talking to you! It’s been a fascinating conversation.